The moment arrives differently for every family. Maybe it’s when your seventh grader bursts into tears over homework that “doesn’t make sense.” Maybe it’s the first time you see a string of letters mixed with numbers and realize you can’t help anymore. Or maybe it’s just that sinking feeling when your child - who used to love math - suddenly says, “I’m just not a math person.”

Pre-algebra marks the most significant transition in your child’s mathematical journey. It’s the year when arithmetic becomes algebra, when concrete, familiar numbers give way to abstract thinking, and when students who excelled in elementary school sometimes find themselves completely lost. The beginning of the pre-algebra journey is crucial, as these early stages lay the foundation for all future math learning.

Here's what you need to know: You don't need to re-learn pre-algebra to support your child. You don't need to become their teacher. But you do need to understand what's happening, recognize when normal struggle crosses into serious difficulty, and know what you can realistically do to help.

This guide focuses on your role as a parent—not as a math tutor. We'll walk you through what pre-algebra actually is, why it feels so hard, what support you can provide at home, and most importantly, how to recognize when your child needs more than homework help.

Pre-algebra is the bridge between the arithmetic your child has been doing since kindergarten and the abstract reasoning that will define their mathematical future. In elementary school, math problems have concrete answers. 5 + 3 = 8. Always. The numbers represent actual quantities - five apples, three more apples, eight total apples.

Pre-algebra changes everything. When your child sees “x + 3 = 8,” they’re no longer just calculating - they’re reasoning. That “x” represents an unknown quantity, a placeholder for something they need to figure out. This shift from concrete to abstract thinking is fundamentally different from anything they’ve encountered before. Teachers now describe how new concepts are introduced, connecting prior learning and preparing students for future work by providing clear, detailed explanations of the instructional process.

Most students take pre-algebra in middle school, i.e., 6th, 7th, or 8th grade - ages 11-14, precisely when the brain is developing capacity for abstract reasoning. Your child isn’t just learning new math; their brain is literally building new cognitive pathways.

Here's what you need to understand as a parent: Pre-algebra is called the “gateway course” because every math class that comes after - Algebra I, Geometry, Algebra II, and beyond - assumes mastery of these concepts. College counselors report that more students abandon STEM majors because of shaky pre-algebra foundations than for any other single reason. Pre-algebra skills lead directly to success in later math courses, providing the logical progression needed for advanced topics and real-world applications.

If you’re in your 30s or 40s, your pre-algebra looked different. You learned procedures: memorize the steps, apply the formula, get full credit. Today’s pre-algebra - especially in Common Core curricula - emphasizes the why behind the how. Teachers expect students to explain their reasoning, show multiple solution paths, and demonstrate conceptual understanding. Lessons are now structured to build understanding in a coherent, standards-aligned progression, often including opportunities for reflection and embedded supports.

This frustrates parents endlessly. “The answer is right - why does it matter how they got there?” But here’s what modern math education understands: students who only memorize procedures forget them the moment the test ends. Students who understand underlying concepts can apply them in new situations and build toward higher mathematics.

Real-World Connections

When pre-algebra clicks, students start seeing mathematical patterns everywhere. Gaming provides endless examples: calculating damage-per-second in RPGs involves rates and ratios. For example, if a character deals 120 points of damage over 3 seconds, students use division to find the rate - 40 points per second - connecting a real-life gaming scenario to the concept of rates. Managing Minecraft resources requires proportional reasoning. Understanding Fortnite win rates means working with percentages.

Sports-obsessed kids explore batting averages and fantasy football projections. Social media natives analyze follower growth rates and engagement percentages. Students earning money calculate hourly wages and compare sale discounts.

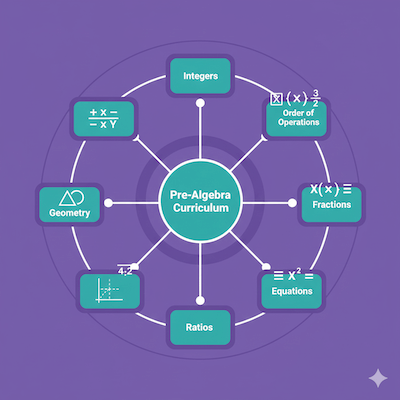

Pre-algebra curriculum varies by district, but most courses cover these core areas. Rather than teaching these topics yourself, your role is understanding what your child is learning so you can:

Integers and Negative Numbers: Your child will work with integers, negative numbers, and rational numbers. This is harder than it sounds—negative numbers don't represent tangible quantities the way positive numbers do.

Home support focus: Help them find real-world examples. Temperature below zero makes sense to kids (especially if you live somewhere cold). Bank account debt, elevation below sea level, golf scores—these contexts make abstract negatives concrete.

If they're really struggling with this: The Parent's Guide to Teaching Positive & Negative Integers

Variables and Algebraic Expressions: This is the big cognitive shift—moving from concrete numbers to abstract placeholders. Many students initially think variables are abbreviations or that each letter always represents the same number.

Home support focus: Don't try to teach this differently than their teacher. Modern teaching uses multiple models (balance scales, tape diagrams, "mystery boxes") to build understanding. Instead of reteaching, ask your child to explain their thinking: "Walk me through how your teacher showed you to solve this."

Deep dive: Understanding What is a Variable in Math: A Comprehensive Guide

Order of Operations: The PEMDAS/GEMDAS debate causes homework battles when parents are certain of an answer but the textbook shows something different. Modern interpretation emphasizes that multiplication and division have equal priority (work left to right), as do addition and subtraction. [What Is PEMDAS? A Parent-Friendly Guide to the Order of Operations]

Fractions, Decimals, and Percentages: Here's a hard truth: many students enter pre-algebra without truly mastering fractions from elementary school. This matters because fractions appear everywhere—in solving equations, calculating rates, understanding probability, and eventually, finding slope.

Home support focus: If your child struggles here, this needs targeted intervention. Fraction weakness will derail almost everything in pre-algebra.

If fractions are the issue: How to help your 6th grader with Fractions at home

Ratios, Proportions, and Rates: These connect math to everyday situations—recipes, maps, unit pricing, speed calculations. The math looks simple but requires sophisticated proportional thinking.

Home support focus: Point out proportional thinking in daily life. "If this recipe serves 4 but we need it for 6, how much flour do we need?" Or at the grocery store: "Which size is a better deal?"

Real world examples: Mastering Proportions: Real World Examples to Explain Ratios and Rates

Linear Equations: Students learn systematic equation-solving and—the part that trips up most students—translating word problems into mathematical language.

Home support focus: Encourage showing work and explaining reasoning, not just getting answers. When they're stuck on a word problem, use the three-question framework (more on this in Section 5):

Step-by-step help: Solving One-Step Equations: Your Child's First Step into Algebra

Word problem strategies: Solving Word Problems

Here's liberating news: You don't need to re-learn pre-algebra to support your child. Modern teaching methods differ from what we learned, and trying to teach "your way" often creates more confusion than clarity.

Your job is to:

For detailed curriculum coverage and what professional tutoring addresses: See what Ruvimo's pre-algebra program covers

Between ages 11 and 14, the brain undergoes significant development in the prefrontal cortex—the region responsible for abstract thinking. Pre-algebra coincides with when students' brains are becoming capable of this thinking, but capability doesn't mean mastery.

Research confirms what teachers see daily: approximately 40% of students experience a noticeable drop in math confidence during 6th and 7th grade. This isn't because these students lack ability—it's because cognitive demands increased dramatically while abstract reasoning skills are still developing.

Think of it this way: Elementary math is like walking on solid ground. You can see where you're stepping. Pre-algebra is like learning to swim—you can't see or touch the bottom anymore, and that's disorienting. Some kids adapt quickly. Others need more time and support to feel safe in deep water.

Even parents who were math whizzes face unique challenges helping with pre-algebra:

You Learned It Differently

Common Core emphasizes understanding multiple solution paths, not just memorizing procedures. When your child shows you how their teacher solved a problem, it might look completely foreign—and that's by design.

Example: You solve 3x + 5 = 14 by "moving the 5 to the other side." Your child's teacher talks about "maintaining balance" and "inverse operations." Same result, completely different framework. Neither is wrong—they're just different languages for the same concept.

The Teaching Language Has Changed

Terms like "number sentences," "think boards," "tape diagrams," and "area models" weren't in your math education. Your child's textbook might feel like it's written in another language. That's because it is—the language has evolved to emphasize conceptual understanding.

Your Emotional Investment Gets in the Way

When you're frustrated that your child "just doesn't get it," that frustration leaks through. You might not say anything, but kids are emotional ninjas—they pick up on your stress, and it becomes their stress.

Professional tutors maintain patience because it's not their kid—there's no emotional baggage, no worry about what this means for college applications, no fear that struggling in 7th grade math predicts their entire future.

Bottom line: If pre-algebra homework is creating tension in your home, that's a sign to adjust your approach—not a reflection on your parenting or your child's ability.

"I'm just not a math person" appears with alarming frequency around 6th-7th grade. Middle school is when students start forming fixed beliefs about their abilities. Students who believe intelligence is fixed give up more quickly when challenged.

Here's what makes this worse: Gender differences in math confidence emerge sharply during these years, despite no actual difference in ability. Girls, especially, begin opting out of math-intensive courses based on confidence, not competence.

What parents must do: Your response to struggle matters enormously. Research shows that parents' math attitudes predict children's math attitudes and achievement, independent of actual ability.

Never say:

Instead say:

Many students enter pre-algebra without truly mastering elementary arithmetic. Students who aren't automatic with multiplication tables struggle with factoring. Weak fraction skills derail equation solving. Poor decimal understanding hampers percentages.

What to do: Diagnostic assessment without judgment. Five minutes daily of targeted practice on weak areas beats hours of random review. When it's serious: If basic operations aren't automatic, these gaps will completely prevent pre-algebra success. Professional tutoring that explicitly addresses foundational skills becomes essential.

For many students, this is where math stops making sense. Students often think each letter always represents the same number, or that letters are abbreviations. The mental shift to understanding variables as placeholders for unknowns is genuinely difficult.

What helps: The "mystery box" analogy - "Imagine a box containing something unknown. We call it 'x.' If three of these boxes plus five loose items equals fourteen total items, what's in each box?" When it's serious: If your child can't explain what a variable represents or evaluate simple expressions after multiple weeks, they've hit a conceptual wall requiring patient, systematic instruction.

Word problems require translating English into mathematical notation. Students must read the scenario, identify knowns and unknowns, determine relationships, translate to equations, solve, and interpret results. Many freeze at step two or three.

What helps: A three-step process: (1) What do you know? (2) What do you need to find? (3) How are they related? Breaking it down systematically removes paralysis. When it's serious: If your child solves equations easily but completely freezes on word problems, they need explicit translation strategies. [Solving Word Problems]

Rules for negative numbers feel arbitrary because everyday experience with quantities is almost entirely positive. Students struggle especially with "why does negative times negative equal positive?" Real-world models help: temperature changes over time, debt forgiveness, video playback in reverse. When it's serious: If your child is in 7th-8th grade and still struggling with integer operations, this will sabotage everything in algebra. These skills must become automatic.

Math anxiety - characterized by tension, fear, and physical symptoms around math - emerges most commonly in middle school. Students develop it through repeated failure without support, timed tests prioritizing speed, social comparison with peers, and perfectionism making any mistake feel catastrophic.

What parents must do: Your response matters enormously. When parents express their own math anxiety ("I was never good at math either"), children's anxiety increases and performance decreases. Instead, normalize struggle ("This is challenging AND you can learn it"), praise process not intelligence, and separate performance from identity. When it's serious: Physical symptoms before math class, frequent emotional meltdowns, or complete avoidance requires urgent intervention.

This is where the rubber meets the road. What can you actually do to help?

Children absorb parents' attitudes about mathematics like sponges absorb water. Research shows parents' math attitudes predict children's math attitudes and achievement, independent of actual ability.

Replace these phrases:

"I was never good at math either"

"Math was challenging for me, but I wish I'd had better resources"

"When will you ever use this?"

"Building problem-solving skills helps you think clearly about all kinds of situations"

"Just get it done"

"Show me what you've tried so far"

"This is too hard for you"

"This is challenging right now—let's break it down"

Create a growth mindset wall: Post examples of people who failed before succeeding. Michael Jordan was cut from his high school basketball team. Einstein struggled in school. J.K. Rowling was rejected by 12 publishers. Add your child's own "math victories"—no matter how small.

Celebrate struggle: "I can see you're working hard on this. Your brain is growing right now—that's what learning feels like." This reframes frustration as productive rather than as evidence of inability.

Most parents fall into one of two traps: taking over the problem or giving up too quickly. Here's the middle ground.

The Three-Question Framework

Before touching the problem, ask:

These questions activate your child's thinking without giving away the answer. Often, the act of explaining helps them see the path forward.

The 5-Minute Rule

If you're explaining for more than 5 minutes and your child's eyes are glazing over, stop. You've probably:

Instead: "Let's take a break. Tomorrow, ask your teacher to show you this specific step. Write down exactly what's confusing you."

Example Dialogue:

What NOT to do: Parent: "Okay, so first you subtract 5 from both sides, then you divide by 3..." Child: glazed stare, nods without understanding

What to do instead: Parent: "Walk me through what your teacher showed you in class." Child: "I don't remember." Parent: "What do you remember? Even just the first step?" Child: "She said something about doing the same thing to both sides..." Parent: "Great start! What do you think 'the same thing' means here?" Child: "Like if I subtract from one side, I have to subtract from the other?" Parent: "Exactly! So what would you do first in this problem?"

See the difference? The second conversation activates the child's thinking and builds on what they already know rather than explaining from scratch.

The 20-Minute Rule

If your child has been stuck for 20 minutes with zero progress, stop. Grinding away accomplishes nothing except exhaustion and frustration.

Send a note to the teacher. Write in the margin: "Worked for 20 minutes—couldn't complete." This gives the teacher valuable diagnostic information and prevents homework from destroying your evening.

Related: [Homework Management: 5 Organization Tips for Disorganized Middle School Math Students]

Forget the textbook's "real-world examples" (train problems, swimming pools filling at different rates). Use your child's actual interests:

For the gamer:

For the athlete:

For the artist:

For the social media native:

The key: Don't force it. When these situations arise naturally, point out the math: "Hey, you just solved a proportion problem!" This builds recognition of math's usefulness without making it feel like extra homework.

Here's what neuroscience tells us about learning math:

20 minutes daily beats 2 hours the night before a test—by a huge margin.

This "spacing effect" is one of the most robust findings in learning research. The brain needs time between practice sessions to consolidate learning. When you cram, information goes into short-term memory and exits just as quickly.

The practical homework schedule:

Monday-Thursday: 20-30 minutes of homework + 10 minutes reviewing previous concepts

Friday: Review the week's topics (no new material)

Weekend: ONE practice test or problem set (not 3 hours of catch-up)

How to build this routine:

Week 1: Establish the time and place

Week 2: Add the structure

Week 3: Add the spacing

What derails this routine:

Related: [Building Study Habits That Actually Stick: A Middle School Parent's Guide]

Sometimes the most supportive thing you can do is... step back.

Signs you should stop helping:

Alternative support strategies:

Passive support (you're still helping, just differently):

Peer support:

Teacher connection:

Professional intervention:

Remember: There's no shame in recognizing that your help isn't helping. In fact, that's advanced parenting—knowing when to change strategies.

If homework has become a nightly battle that's straining your relationship with your child, that's a sign that a different approach is needed.

You've tried everything in this guide. You've created a math-positive environment, provided consistent structure, asked good questions instead of giving answers. But something still isn't clicking.

Here's how to know when it's time to bring in professional help.

Try the strategies in this guide consistently for three weeks. Track:

After three weeks:

Things are improving: Keep doing what you're doing

No change: Schedule a teacher conference to discuss additional resources

Things are getting worse: Professional intervention needed now

Some red flags can't wait three weeks:

Academic crisis markers:

Emotional crisis markers:

Behavioral changes:

When you see these patterns, act immediately. These aren't "growing pains"—they're distress signals that your child needs support beyond what you can provide at home.

Level 1: School resources (START HERE)

Level 2: Skill-specific intervention

Level 3: Professional tutoring

Here's what's different about professional support:

Diagnostic expertise: Tutors quickly identify the specific gap causing current struggles. Is it really pre-algebra, or is it actually fraction weakness from 5th grade? Integer confusion? Word problem translation skills? Parents see the symptoms; tutors diagnose the root cause.

Systematic gap-filling: They know the exact sequence to teach concepts so learning sticks. It's not just "practice more"—it's identifying prerequisite skills and building them in order.

Emotional distance: No parent-child baggage. Students often accept feedback from tutors they'd resist from parents. There's no emotional load around disappointing mom or dad.

Specialized knowledge: Pre-algebra tutoring requires understanding both the content AND how 11-13-year-olds think. That's specialized expertise developed through hundreds of hours working with middle schoolers.

Consistent accountability: Weekly sessions create structure that's hard to maintain at home amid busy schedules and family dynamics.

Multiple explanation approaches: If one way doesn't click, they immediately try another. They have a toolkit of metaphors, visuals, and examples built from teaching hundreds of students.

For detailed information about how pre-algebra tutoring works: Explore Ruvimo's Pre-Algebra Tutoring Program

Here's the hard truth: In mathematics, gaps compound. A student who doesn't master pre-algebra:

Early intervention prevents this cascade:

Address struggles in 7th grade → One year of support typically achieves mastery

Wait until 9th grade → Two to three years of remediation needed

Wait until 11th grade → Often too late for full recovery; STEM paths likely closed

The question isn't "Can we afford tutoring?"

The question is: "Can we afford NOT to address this now?"

Every week of accumulated frustration makes intervention harder and recovery slower.

You know your child better than any teacher, tutor, or article. If something feels off—if the light has gone out of their eyes around math, if they're working twice as hard for half the results, if your smart, capable kid suddenly seems lost—trust that instinct.

You don't need to wait for failing grades. You don't need teacher permission. If you sense your child needs more support than you can provide at home, you're probably right.

Ready to explore whether tutoring is right for your child?

Schedule a free consultation to discuss your specific situation

You've read a comprehensive guide—now what? Here's your step-by-step action plan based on where your child is right now.

Focus on prevention:

Week 1: Implement the "math-positive environment" strategies—audit your math language, post a growth mindset wall

Week 2: Establish consistent homework routine using the spacing principles

Week 3: Practice the three-question framework for homework help

Ongoing: Point out mathematical connections in their interests

Bookmark these articles for when specific topics arise:

Take action this week:

Day 1-2: Start the three-week test—create a simple tracker:

Day 3: Email teacher requesting meeting. Include:

Day 4-7: Implement roadblock-specific strategies from Section 4 based on where your child is stuck

Week 2: Assess what's working:

Week 3: Decide on next level of support:

Act immediately:

Today:

This week:

This month:

Almost every parent of a middle schooler has stood where you're standing—watching their child struggle with math that seems impenetrable, wondering if they should help more or step back, questioning whether this is normal difficulty or a sign of something bigger.

Here's what we know after working with hundreds of families:

The struggle is real. Pre-algebra represents a genuine cognitive leap. Your child isn't lazy or incapable—they're developing new ways of thinking. Their brain is literally rewiring itself to handle abstract reasoning.

Your support matters. Even when you can't teach the math, your attitude, structure, and encouragement shape your child's mathematical identity. How you respond to struggle matters more than whether you know how to solve for x.

Knowing your limits is a strength, not a failure. The parents who get the best outcomes aren't the ones who know the most math—they're the ones who recognize when to adjust their approach. Stepping back isn't giving up; it's making a strategic decision about what your child needs.

Early action prevents years of struggle. Every week you address difficulties is a week saved from more intensive remediation later. Intervention in 7th grade is infinitely easier than remediation in 10th grade.

You've equipped yourself with understanding and strategies. Now trust yourself to recognize what your child needs—whether that's consistent encouragement at home, school resources, or professional tutoring—and take action accordingly.

Your child's mathematical future—and all the doors it opens—is shaped by the foundation they build right now.

And that foundation doesn't require you to know pre-algebra. It requires you to know your child, maintain perspective on what really matters, and get them the support they need when home help isn't enough.

Q: Can I teach pre-algebra to my child at home if I don't remember it myself?

A: Short answer—you don't need to. Your role isn't to reteach concepts; it's to provide support, structure, and encouragement. Use the strategies in Section 5 that don't require you to know pre-algebra yourself. If your child needs actual instruction on concepts, connect them with their teacher, online resources like Khan Academy, or professional tutoring.

Q: How much time should pre-algebra homework take?

A: General guideline is 30-45 minutes per night for most students. If it's consistently taking 60+ minutes, something's wrong—either the workload is too heavy, foundational gaps exist, or your child is stuck on concepts they haven't mastered. After three nights of unusually long homework sessions, email the teacher with specific details about what's taking so long.

Q: My child's teacher uses methods I don't understand. Should I teach them the "old way"?

A: No. This creates confusion and undermines the teacher's instruction. Modern methods emphasize understanding (which builds long-term retention) rather than memorization (which fades quickly). If you're curious about why teachers use certain methods, ask! Most are happy to explain. But don't teach conflicting approaches—it forces students to switch mental frameworks, which makes everything harder.

Q: Is it normal for my confident student to suddenly struggle?

A: Absolutely. Pre-algebra is precisely where this happens for many students. The cognitive leap from concrete to abstract thinking is significant and affects even students who previously excelled. What's important is how you respond—normalize the struggle ("Pre-algebra is hard for a lot of people"), maintain encouragement, and get support if difficulties persist beyond 3-4 weeks.

Q: When should I contact the teacher about math struggles?

A: Contact immediately if:

Include specific information in your email: "Jake spent 45 minutes on the 10-problem assignment and completed only 3 problems. He seems stuck on understanding how to set up equations from word problems. Can we discuss what support is available?"

Q: My child hates math. Is it too late to change that?

A: It's never too late, but it requires intentional effort. Start with changing the narrative at home (Section 5—audit your math language), connect math to their interests, celebrate small wins rather than focusing on grades, and if necessary, get support that rebuilds confidence alongside skills. Many students who "hated math" in 7th grade develop genuine interest by 9th grade with the right support system.

Q: How is pre-algebra different from Algebra 1?

A: Pre-algebra introduces concepts at a basic level with significant scaffolding and slower pacing. Algebra 1 assumes you've mastered those foundations and moves much faster into complex applications. Think of pre-algebra as learning to swim in the shallow end with floaties and an instructor nearby; Algebra 1 assumes you can swim and puts you in the deep end immediately. The gap between the two is why solid pre-algebra mastery is so critical.

Q: What if my child has a learning disability?

A: Many students with diagnosed learning differences (dyscalculia, ADHD, processing speed issues, working memory challenges) can absolutely succeed in pre-algebra with appropriate support. Inform the teacher about the diagnosis and ensure your child receives accommodations in their IEP or 504 plan. Professional tutoring that's specifically adapted for learning differences can be extremely effective—tutors can adjust pacing, use multi-sensory approaches, and provide the extra repetition and review needed.

Teacher Christi is an engineer and educator currently teaching at a leading state university in the Philippines. She is pursuing a Master of Science in Teaching (Physics) and is also a licensed professional teacher in Mathematics. With a strong foundation in engineering, physics, and math, she brings analytical thinking and real-world application into her classes. She encourages hands-on learning and motivates students to view mathematics as a powerful tool for understanding the world. Beyond the classroom, she enjoys reading and exploring history, enriching her perspective as a dedicated academic and lifelong learner.